I originally started writing this article with the premise of how to improve one’s bench press. Then I thought how extremely redundant and limiting that idea has become. How many articles have we all read promising huge gains in our bench, but with further examination we see it is just another bodybuilding routine?

Plus, if we as lifters only improve our bench that leaves many other aspects of training left behind. For example, how good of an athlete will you be in you can only bench press, or how great of a bodybuilder will you become only having a chest? So, instead, I thought I would focus on three of the most important lifts instead, the bench press, deadlift, and squat.

Why I chose these particular lifts is very easy to explain. They are at the core of developing any type of strength training program. Because of their ability to develop the overall body, the should be thought of the essential lifts for anyone interested in increased athletic performance, strength, power, physique transformation, or advanced rehabilitation.

In the following series of articles, I have discussed some of the most effective ways of improving these lifts. However, this article is going to be a little different than previous articles you may have read. Science and sound training philosophy will back this article not solely my personal experience as a strength coach.

Health History:

When embarking on a program involving the big three lifts it is vital to examine someone’s health history. Have they experienced injuries that could alter their technique or make it an unwise choice to even utilize these exercises?

There is a great saying about exercise selection, “there is no such thing as a bad exercise, only the inappropriate usage of an exercise.”

If you are healthy enough to perform these movements, then looking at what injuries you have suffered previously will give us insight into where to begin. Many times injuries to the head and neck region will cause a significant loss in strength because of the many nerves that bypass this region. I always encourage those that have suffered injuries in the head and neck to make sure their spinal alignment is good and their soft-tissues are healthy.

Both of these structures are needed to ensure proper transmission of nerve impulses throughout the body. The National Institute of Health found that the weight of a dime compressing a nerve can cause a decrease of 40% of nerve strength and power!! This can cause significant weakness in different movements.

We must also examine the shoulder, low back, and hip structures. Old injuries may have caused scar tissue to develop in these structures altering proper movement patterns.

In this case, I would advise the lifter to seek out a skilled soft-tissue therapist. Active Release Techniques have been shown to be very effective in removing these scars to allow increased mobility. Structural damage to these areas such as dislocations or disk damage must be fully evaluated. If these injuries are still persistent then I would be weary of the weights used and make sure these areas are healthy before trying to break any new records.

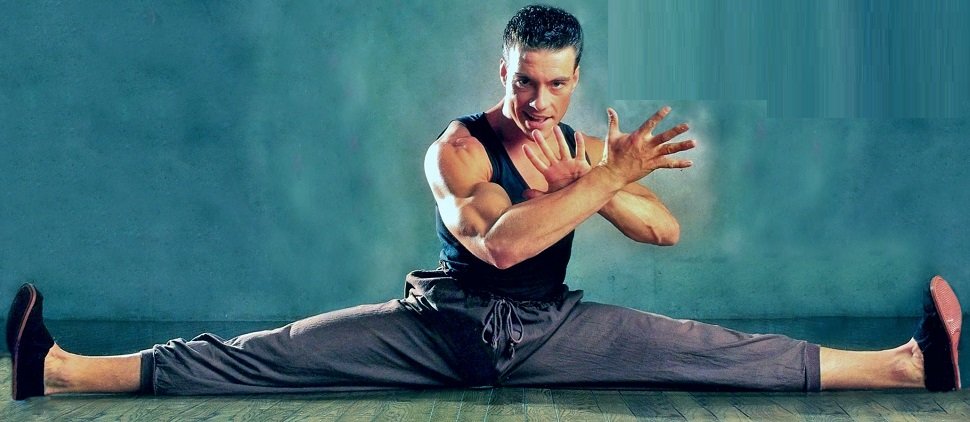

Flexibility:

Stretching may be one of the most boring aspects of training. However, it is crucial to have a proper range of movement for these lifts. From personal experience, I have had clients improve 10-15% percent in their lifts just from an improved range of motion. Discussions with World-Renown Strength Coach, Charles Staley, have also confirmed my findings.

Coach Staley has also had situations where athletes break personal records from just improving the flexibility in the tight structures.

From my experience, these muscles can attribute to disrupting one’s ability to reach their full potential in the big three lifts.

- Bench: Serratus anterior, pec minor/major, rotator cuff, latissimus dorsi, long head of tricep, biceps

- Deadlift: Hamstrings, external hip rotators, glutes, low back, hip flexors, and calves

- Squat (Olympic style): Hip flexors, calves, external hip rotators (especially piriformis), and low back

Technique:

This may seem like a no brainer, but you would be surprised at how many coaches are unable to teach basic lifts like the bench, squat, and deadlift. Plus, having been in many gyms it is obvious to me that many of the best-intentioned lifters have never learned the fundamentals of the big three.

The description of each lift could go on for pages so I am going to touch over the basic mistakes individual lifters commit during the performance of these lifts.

Bench Press:

- Feet are not firmly placed on the ground and at least bent 90 degrees in relation to the upper thigh.

- No arch placed in the thoracic spine. Many lifters may argue with this technique as solely being that for powerlifters, but I find it increases the usage of the lats and helps stabilize the shoulder joint.

- The bar does not start over the place where it will land. For increased strength purposes the bar should start over the lower aspect of the chest and touch the lower part of the sternum.

- Not pulling back the shoulders before the descent of the bar.

- Not pressing through the bench with the body.

- Not using a Valsalva maneuver (where one purposefully holds their breath for increased strength past the sticking point) to blast past the sticking point.

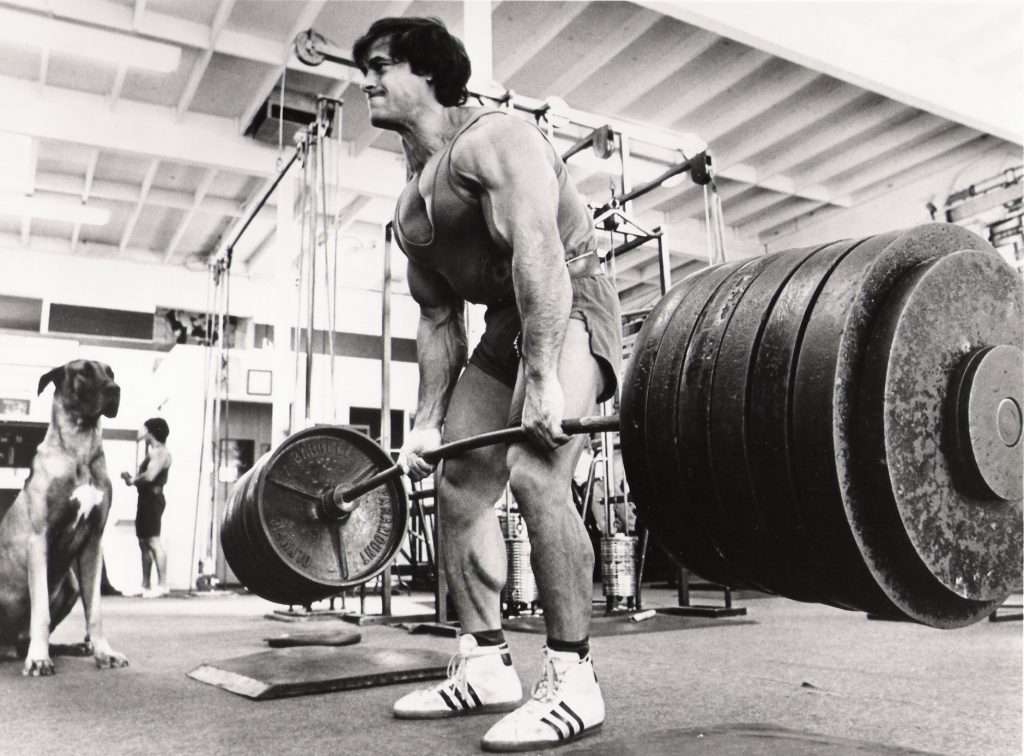

Deadlift:

- The bar starts too far from the shins.

- The movement is initiated by the hips rising instead of the knees moving back.

- The upper back is too rounded and the shoulder blades are not being actively pulled back.

- The bar drifts away from the body during the raising of the weight.

- The descent is not supposed to be done the reverse of the concentric and if it is will throw off the lifter.

- Not consciously pushing through the floor instead of trying to raise the weight with the low back.

Squat:

- The bar should be just below C7 (the very bony vertebrae of the neck) and the elbows should be pointing straight down with the hands as close to the shoulders as possible.

- Hips should be hip-width or just slightly wider with the feet pointing out no more than 30 degrees.

- The movement should be initiated by bending of the knees than the hips. This is to prevent too much initial forward lean.

- The knees should be actively pushed out by the lifter to help with strength and to avoid the knees falling inwards in relation to the thigh.

- Pushing up should not cause the torso to automatically increase its forward lean. The push should allow one to remain relatively upright.

- The flexibility and goal of the lifter dictate the depth. Most times I will not want to squat at least parallel, more ideal is below parallel. If you can not go this deep determine if it is due to flexibility issues or the fact you that are using too much weight!

Leave a Reply